The Power of the Harmonic Series in Music

1. A Guitar Doesn’t Sound Like A Flute 🎸

The harmonic series is a phenomenon that is responsible for most of Western music theory. Not only is it what music is based on, but it can also help us understand why certain notes, chords and sounds are pleasing or not-so-pleasing to listen to!

When we play a note on any instrument we are actually hearing the sound produced from a vibration and the speed of that vibration determines the pitch (or the note) that we hear. For example an “A“ in the middle of a piano is 440 hertz which means it’s vibrating 440 times per second!

However, when we play a note we don’t just hear the one note. We actually hear lots of notes stacked on top of each other, these notes are much more faint and are called harmonics! It’s the harmonics that give us the quality of sound (or timbre) that we hear. A guitar playing an “A” will vibrate 440 times per second but will have some “overtones” that are more pronounced than others, whereas a flute playing an “A” will also be vibrating 440 times per second but will have different “overtones” that are pronounced and this is what gives each instrument a different quality of sound!

2. Why Twelve? 👨🏻🔬

Not only does this natural phenomenon determine how different instruments sound but it is also what has come to determine a lot of how we think about music and in particular, how we divide up the notes. In modern Western music we divide music up into 12 notes (although humans are actually capable of distinguishing 240 different notes). Firstly, from one “A” to the next “A” we simply double the speed of the vibration, so we can find the note A at 440 hertz but we can find another A at 880 hertz and another at 1760 hertz!

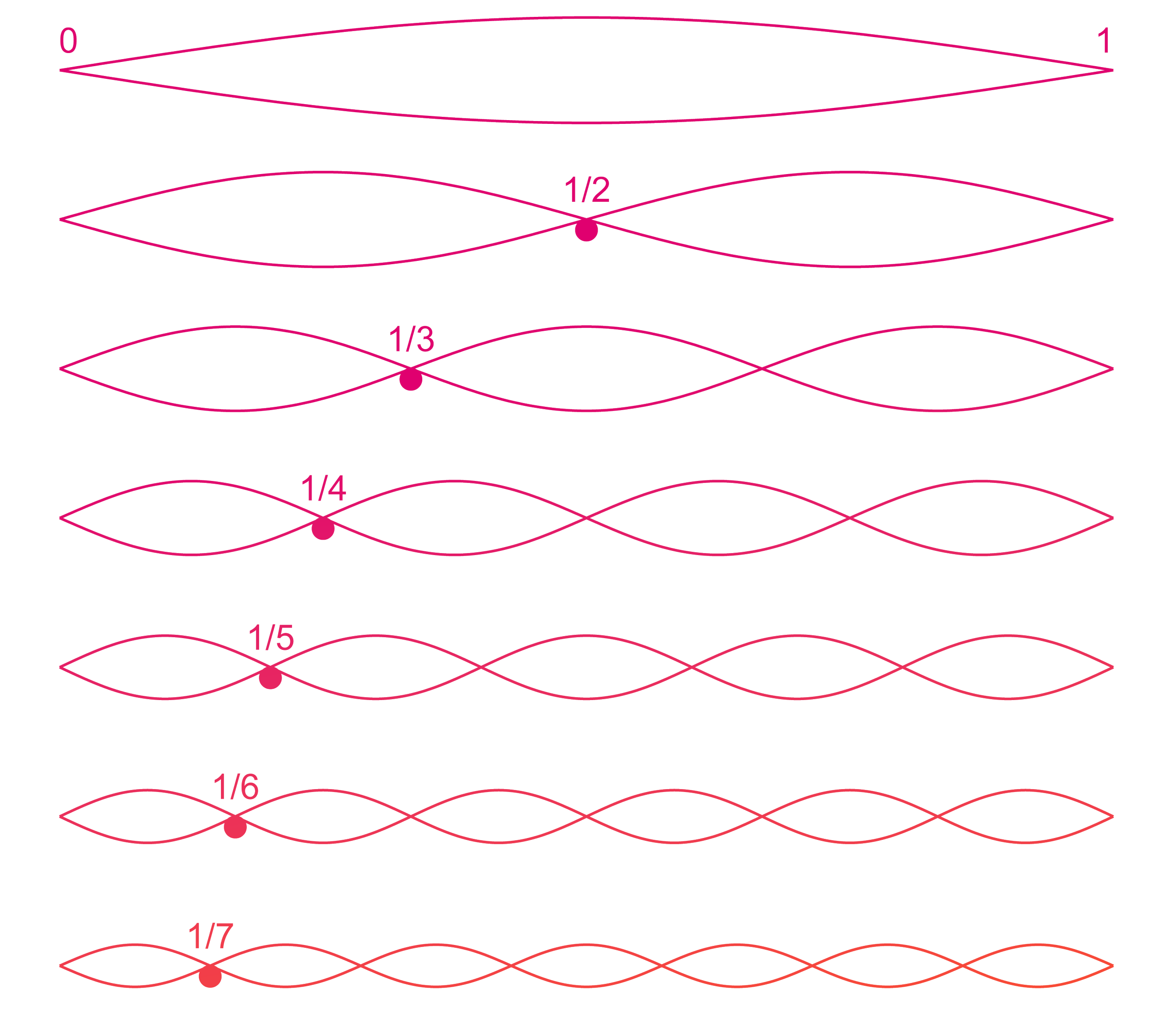

This is why these notes sound so strong together, because if I were to play two different A’s on the piano..they naturally vibrate together meeting at regular intervals. The less frequently the vibrations meet, the more dissonant they will sound.

The second closest note in the harmonic series are notes that are 5 notes apart, and so naturally we call these “fifths”. It is this relationship that gives us all of the key signatures and the 12 notes that we have in Western music. We can find an A at 440 hertz, 5 notes above this is the note E which is approximately 660 hertz and this is 1.5x the vibrations of the note A. So these notes also regularly synchronise, meaning that an A and an E sound very consonant and strong when played together. If we follow this logic again from the note E, 5 notes above an E is a B (which is approx 990 hertz, also 1.5x the frequency) and these notes played together will also sound quite strong and consonant.

Continuing this process over and over again gives us 12 notes before arriving back at another A and this is called the “circle of fifths”! This is how Western music has arrived at dividing notes into a series of 12 equal notes.

This is also what has given us the different scales in music. A scale is simply a way that we can describe how notes relate to each other. So if note 1 in a scale is A, note 5 in the scale is an E (which is 1.5x the frequency). If note 1 in the scale is C, then note 5 in the scale is a G (which is also 1.5x the frequency). All of the notes in a C major scale relate to each other in exactly the same way is all of the notes relate to each other in all of the other major scale.

3. Good vs. Bad Music 🎺

The harmonic series is actually very predictable, we hear lots of overtones when we play any note but these overtones are the same relationship to the original note each time and the further away the overtone the less close the note relationship is!

Knowing that it is the frequencies of notes and how well those frequencies fit together is what determines how consonant/strong or dissonant/weak we perceive the notes to be can start to help us understand how we can use different note relationships to make music and more specifically, chords.

Order of relationship strength:

- OCTAVES

- FIFTHS/FOURTHS

- THIRDS

- SECONDS

- CONSECUTIVE NOTES (SEMITONES/HALF STEPS)

This means that when we form chords, we can form strong sounding chords using OCTAVES, FIFTHS and FOURTHS, but we can create weaker chords that have a much more nuanced sound using THIRDS and SECONDS. If we want to create very weak and much less stable chords then we can use SEMITONES/HALF STEPS because these frequencies don’t synchronise very frequently at all!

4. What Does This Mean? 🤷🏻

The science and physics of frequencies is very fascinating and very helpful. Having said this, thinking about what frequencies notes are is impractical and not in itself important for music learning.

However, understanding why different instruments have different qualities of sound, why we have 12 notes and how these notes relate to each other to form scales and chords and which note relationships feel stronger and weaker can all endlessly improve your toolkit when it comes to making, interpreting and enjoying music.

Although music can appear to be magical and like there is so much mystery behind the art. Ultimately, all of the music theory we have come to understand is a product of nature and when we understand natures role in music, we can really start to use it to play music in full control of the effects we want to create!

Matthew Cawood

(This is from my “Monday Music Tips“ weekly email newsletter. Join my mailing list to be emailed with future posts.)